But music notation defied Western theorists and musicians until about 850 AD.

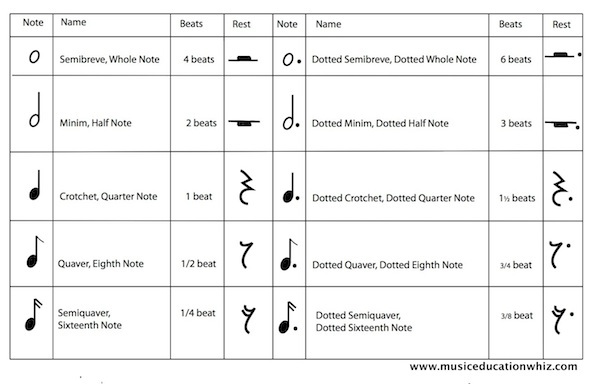

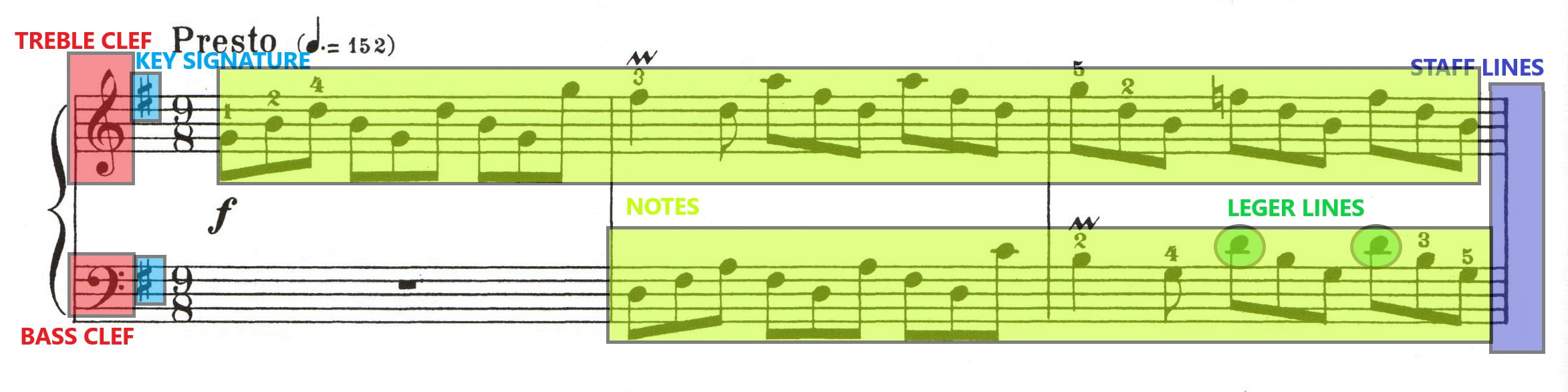

Ways of writing music developed independently in various times and places, from Babylon in 2000 BC to Greece some one and a half millennia later. In practice, very little of it can be written, and what can has been condensed, for all its complexities, into as simple a music notational system as remains practical, developed, with some discontinuity, over the course of centuries. After all, a novel isn’t composed solely in the author’s mind, nor is an entire symphony in its every detail. Yet were it not for written music, we would have neither a preserved musical tradition nor many of its largest and greatest works. We classical musicians tend to be trained with the implicit ideology of textual literalism – some even going so far as to say that the sloppier Beethoven’s handwriting, the more impassioned the music – over music as sound, which is by its very nature immaterial. Music is sound, not black notes on a white page. Yet in any translation, some information is bound to become lost. Notating music is thus a translation from one sensory modality to another.

“Music notation” is a contradiction in terms.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)